All about Auto Row: A (very) brief history

July 8, 2009The next Auto Row meeting is coming up tomorrow, Thursday July 9, at First Presbyterian Church at 2619 Broadway (at 27th) from 6 to 8 pm. The postcard, and last month’s news that GM is finally filing for bankruptcy and closing thousands of dealerships, reminded me that I hadn’t yet finished the little Auto Row retrospective I started a while back, shortly before we went to the kick-off meeting for a two-year planning process to define the future of Broadway Auto Row (or “Upper Broadway,” as the City is starting to call it once again), Oakland’s historic automobile dealer district (and our best-known neighborhood landmark!)

As we think about the future of this space, though, I couldn’t help but think back on the past, since I dug up all sorts of interesting tidbits on Auto Row when I was doing neighborhood history research earlier this year. I meant this to be a bit more narrative and reflective, but haven’t had time to sit down with it—so instead it’s just the blow-by-blow history of the corridor. More musings on the future in the next post….

Before Auto Row: Pre-1912

Broadway, of course, was around for decades before Auto Row was established in 1912. In Oakland’s early years, the neighborhood in and around Auto Row was known as “Academy Hill” for the number of schools and universities that dotted it. (The hill itself is now known to most Oaklanders as “Pill Hill” in reference to the hospitals and medical community that now occupy it.) St. Mary’s College, now in Moraga, sat at 30th and Broadway for nearly 40 years (and in fact had a plaque on the old Connell Oldsmobile building to mark the spot of the building they called “the old Brickpile”).

Other Academy Hill institutions included a military academy, a seminary, and in later years an elementary school that sat at 29th and Broadway, now home to Grocery Outlet (and home to Safeway for 30 years before that). The transition to medical uses began fairly early on, too: another early Auto Row establishment was Providence Hospital, started by the Sisters of Providence at Broadway and 26th and later transferred to Sutter Health, which still runs Alta Bates Summit Medical Center on Pill Hill today.

During these years, Oakland did have an Auto Row—but it was located in downtown Oakland in the heart of the commercial district. When residential development (and the auto industry!) took off in the post-earthquake years, though, so did the need for more automobile retailers, so development of a new Oakland Auto Row along Upper Broadway began.

The Early Years: 1912-1925

Auto-oriented businesses began popping up on Auto Row as early as 1912; by 1913 things were in full swing, so the Row is approaching its hundredth anniversary. Initially, the area was referred to as “Upper Broadway Automobile Row” to distinguish it from Oakland’s established 12th Street auto row and San Francisco’s developing auto row along Van Ness, but before long the name was shortened to “Broadway Auto Row,” as the area is still known today. As Oakland developed, the corridor also became a major transit trunk with multiple streetcar lines taking you out to Piedmont, Berkeley, and as far as Kensington.

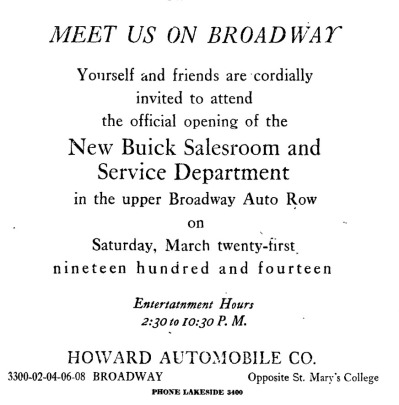

Early tenants included Marion, Studebaker, Empire, A.B. Cosby, J.W. Leavitt, Kissel Kar, Packard, and multiple manufacturers, tire businesses, service stations, and other maintenance and repair shops—not so unlike Auto Row today. By 1914, Buick had opened up shop at Broadway and Piedmont, and was soon followed by virtually every big name in automobiles and automobile parts: Oakland’s Auto Row had arrived.

The new Peacock Motor Company dealership when it opened at 2841 Broadway in 1913. Sadly, it's now a surface parking lot....

Auto Row’s Hey Day: 1925-1955

As Oakland’s population soared in the 1920s through the post-war years, so did Auto Row, as new dealers filled in along Upper Broadway south to Grand and north to West MacArthur Boulevard (then Moss Avenue). Many of the auto-related repair and supply shops that opened up in between the dealerships and along the side streets are still in business today, many incarnations later. Many of the residential areas adjacent to Auto Row also developed in the 1910s and 20s, so there were hundreds of new residents in the surrounding neighborhoods. Mosswood Park, which the City had purchased in 1907, was also extensively developed during this period to include new recreational facilities, amphitheaters, and other community spaces at the northern edge of Auto Row. (Sadly, several of these were later demolished to make room for I-580).

[This section really deserves a much longer writeup, because a lot of cool stuff happened in Oakland and on Auto Row during this period….but since I have zero time to do it right now, it will have to wait for another day!]

The Decline of the City: 1955-1995

By the mid-1950s, the Eisenhower Interstate system was falling into place—and into cities—across the country. In Oakland, existing cross-town thoroughfares expanded into divided roadways, and two new freeways carved out huge swaths of the city, displacing countless residents and fundamentally altering the fabric of many of the city’s neighborhoods. Interstate 580 had a particularly significant impact on Auto Row, as it cut right across the northern edge of Upper Broadway; Interstate 980 also ran parallel to Auto Row a few blocks to the west. As travel to and from the suburbs became faster and easier with the new roads, families—and especially white families—began leaving the city. The streetcars stopped running in the late 1940s, and in 1958, the Key System rail lines shut down. The system was eventually sold in 1960 to the Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District, a newly formed public agency that would manage buses for Alameda and Contra Costa County. Ironically (at least given their own demise as America’s auto fascination waned in recent years!) GM played a major role in bringing down the Key System when its affiliate National City Lines purchased the system in the late 1940s and began pushing to have it shut down. The East Bay cities actually tried to buy the system themselves in the 1950s to keep it running after GM and its associates had been convicted of criminally conspiring to create a monopoly, but they failed….and, as they say, the rest is history.

The 1960 Census also recorded a drop in population for the first time in Oakland’s history. Over the next two decades, the city’s population continued to plummet, falling from a Census high of 385,000 in 1950 to a low of 340,000 in 1980, even as the Bay Area overall continued to grow significantly. By the time the 1980 Census was taken, Oakland was also a majority minority city, with white Oaklanders constituting only 39 percent of the population.

Not surprisingly, Oakland’s Auto Row took an economic nosedive as Americans across the country fled to the suburbs and took their dollars with them. Article after article in the Oakland Tribune during the 1960s and 1970s notes the move of this auto dealership or that parts store to Walnut Creek or Lafayette or parts beyond. During this time, some of the residential areas along Auto Row also deteriorated significantly as homes were razed in some areas and disinvestment spread; the crack epidemic also had a dramatic effect on many of these areas throughout the mid-1980s.

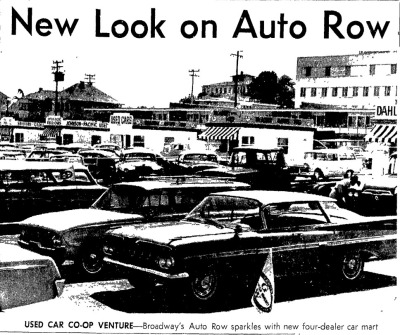

By 1964, both Oakland and Auto Row were in decline. You know it's time to worry when you're excited about the new used car lot that just opened...

The New American City: 1995 and beyond

In the early 1990s, Oakland finally stopped bleeding population, and some areas of the city began to stabilize as new residents trickled in. By the 2000 Census, the population trend had wholly reversed, and for the first time, Oakland exceeded its 1950 population. Much of this growth came in the city’s communities of color: the 2000 Census captured a snapshot of an incredibly diverse city, with a number of new immigrant groups establishing communities in Oakland neighborhoods and contributing to the revitalization of some of the city’s older commercial districts. The housing boom was also ramping up, fueling gentrification in some neighborhoods.

I didn’t live in Oakland during the early Brown years, but friends remember lots of conversations about Auto Row at that point: was there a future for central city auto dealerships? Should Auto Row be expanded northward? What about alternative futures? Streetscape work and new medians shone up the old district, and briefly the future of Oakland’s dealerships looked a bit rosier as some of the big names renovated their showrooms.

Today, of course, it’s another story altogether. Enter the housing bust and the “Great Recession” (as the New York Times has taken to calling it). Some—although notably not all!—of the economic energy in the city has tapered off. Scores of storefronts along the Auto Row corridor are empty; decals for defunct car brands and auto parts stores line the windows next to the “for lease” signs. Chrysler recently severed its franchise relationship with Bay Bridge Chrysler Jeep Dodge, putting them at risk of closing. (Bay Bridge Auto Center, their parent company, also runs the GM and Nissan franchises along this stretch of Auto Row, and seems to do brisk business in used car sales, so they may well hang on for a bit on that front too.) Broadway Ford is already gone, and the Kia building has been sitting empty forever.

I’m not entirely sure this is a bad thing, though. Dedicating a prime commercial corridor near the heart of downtown to auto sales—something the average American buys only once every few years (and, I’d wager, far less frequently in dense urban areas where households may only have a single car, or none at all)—has never made a lot of sense to me. It’s not that I don’t think Oakland should have car dealerships—I do. They bring substantial tax revenues into the city, and are a significant part of our industrial history. It’s just that I don’t think they belong here. It looks like the auto mall on the old Army base may be stalled or dead in the water, but I actually thought that made a lot of sense (as would a similar mall over near Hegenberger, where there are also several dealers). The area along I-880 is already industrial in nature in most spots, and given that car dealers like large surface parking lots and freeway access, it seems like the prime place to drop them.

So what do I want to see on Auto Row instead? I’ll hit that topic next—and you should go to Thursday’s meeting to share your own ideas, whether you live in the neighborhood or not!

[And on that note, this is also a good time to remind folks that yes, lots of people do live in the Auto Row neighborhood—I was a bit taken aback by a few comments from participants at the first meeting who noted that this corridor was a good place for various uses that wouldn’t fly near other residential areas because “the only neighbors are the hospitals and auto shops.” While it’s true that there aren’t too many Pill Hill residents—although even there you’ll find a few condo buildings—there are a lot of residents in Glen Echo, Westlake, HarriOak, Adams Point, and more by the day in Uptown. You can read a little more on the history of these neighborhoods and their relationship with Auto Row here. This doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be regional uses along this corridor—but it does mean that a need for local-serving retail and services also exists, and that any traffic-generating uses will indeed have impacts on residential neighborhoods.]

Great write-up. Interesting stuff, and a good reminder that people do live there.

I really liked this post. Thank you for taking the considerable time to research and write it.

Great post! Thanks for this.